Decoding Language Models

🎙️ Mike LewisBeam Search

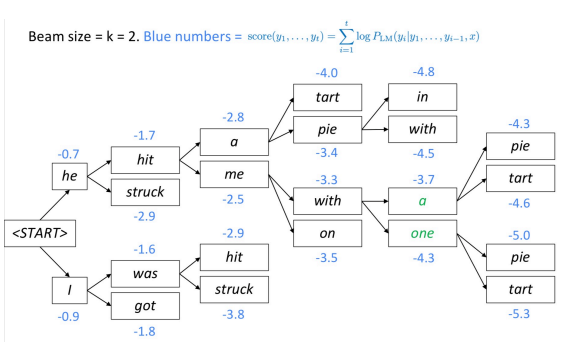

Beam search is another technique for decoding a language model and producing text. At every step, the algorithm keeps track of the $k$ most probable (best) partial translations (hypotheses). The score of each hypothesis is equal to its log probability.

The algorithm selects the best scoring hypothesis.

Fig. 1: Beam Decoding

How deep does the beam tree branch out ?

The beam tree continues until it reaches the end of sentence token. Upon outputting the end of sentence token, the hypothesis is finished.

Why (in NMT) do very large beam sizes often results in empty translations?

At training time, the algorithm often does not use a beam, because it is very expensive. Instead it uses auto-regressive factorization (given previous correct outputs, predict the $n+1$ first words). The model is not exposed to its own mistakes during training, so it is possible for “nonsense” to show up in the beam.

Summary: Continue beam search until all $k$ hypotheses produce end token or until the maximum decoding limit T is reached.

Sampling

We may not want the most likely sequence. Instead we can sample from the model distribution.

However, sampling from the model distribution poses its own problem. Once a “bad” choice is sampled, the model is in a state it never faced during training, increasing the likelihood of continued “bad” evaluation. The algorithm can therefore get stuck in horrible feedback loops.

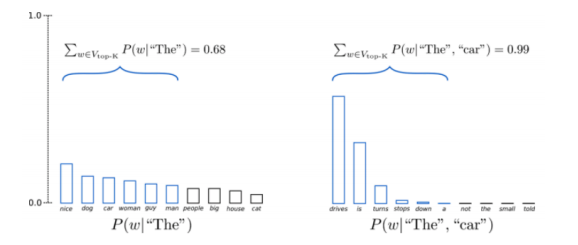

Top-K Sampling

A pure sampling technique where you truncate the distribution to the $k$ best and then renormalise and sample from the distribution.

Fig. 2: Top K Sampling

Question: Why does Top-K sampling work so well?

This technique works well because it essentially tries to prevent falling off of the manifold of good language when we sample something bad by only using the head of the distribution and chopping off the tail.

Evaluating Text Generation

Evaluating the language model requires simply log likelihood of the held-out data. However, it is difficult to evaluate text. Commonly word overlap metrics with a reference (BLEU, ROUGE etc.) are used, but they have their own issues.

Sequence-To-Sequence Models

Conditional Language Models

Conditional Language Models are not useful for generating random samples of English, but they are useful for generating a text given an input.

Examples:

- Given a French sentence, generate the English translation

- Given a document, generate a summary

- Given a dialogue, generate the next response

- Given a question, generate the answer

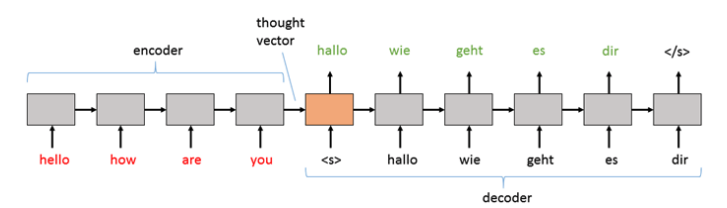

Sequence-To-Sequence Models

Generally, the input text is encoded. This resulting embedding is known as a “thought vector”, which is then passed to the decoder to generate tokens word by word.

Fig. 3: Thought Vector

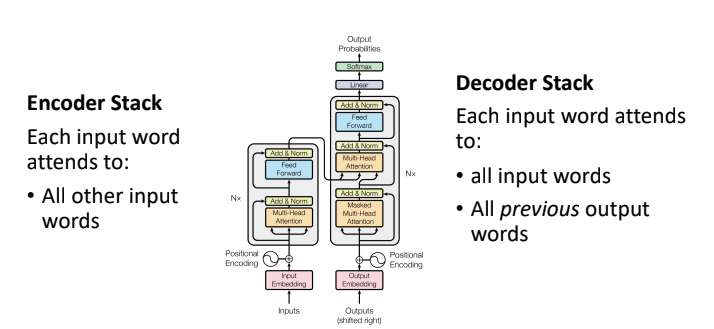

Sequence-To-Sequence Transformer

The sequence-to-sequence variation of transformers has 2 stacks:

-

Encoder Stack – Self-attention isn’t masked so every token in the input can look at every other token in the input

-

Decoder Stack – Apart from using attention over itself, it also uses attention over the complete inputs

Fig. 4: Sequence to Sequence Transformer

Every token in the output has direct connection to every previous token in the output, and also to every word in the input. The connections make the models very expressive and powerful. These transformers have made improvements in translation score over previous recurrent and convolutional models.

Back-translation

When training these models, we typically rely on large amounts of labelled text. A good source of data is from European Parliament proceedings - the text is manually translated into different languages which we then can use as inputs and outputs of the model.

Issues

- Not all languages are represented in the European parliament, meaning that we will not get translation pair for all languages we might be interested in. How do we find text for training in a language we can’t necessarily get the data for?

- Since models like transformers do much better with more data, how do we use monolingual text efficiently, i.e. no input / output pairs?

Assume we want to train a model to translate German into English. The idea of back-translation is to first train a reverse model of English to German

- Using some limited bi-text we can acquire same sentences in 2 different languages

- Once we have an English to German model, translate a lot of monolingual words from English to German.

Finally, train the German to English model using the German words that have been ‘back-translated’ in the previous step. We note that:

- It doesn’t matter how good the reverse model is - we might have noisy German translations but end up translating to clean English.

- We need to learn to understand English well beyond the data of English / German pairs (already translated) - use large amounts of monolingual English

Iterated Back-translation

- We can iterate the procedure of back-translation in order to generate even more bi-text data and reach much better performance - just keep training using monolingual data.

- Helps a lot when not a lot of parallel data

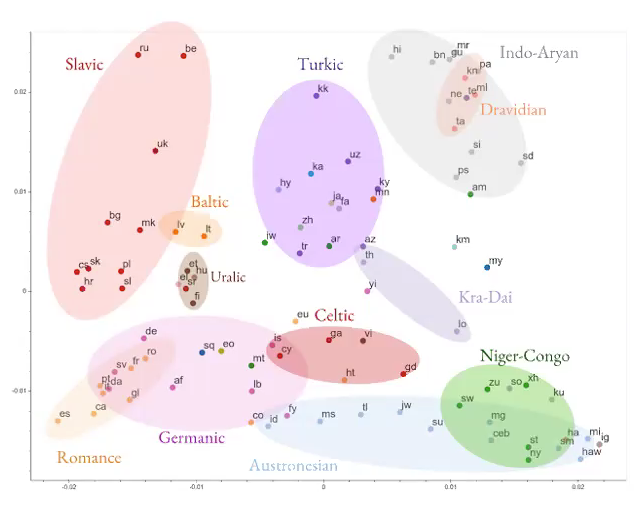

Massive multilingual MT

Fig. 5: Multilingual MT

- Instead of trying to learn a translation from one language to another, try to build a neural net to learn multiple language translations.

- Model is learning some general language-independent information.

Fig. 6: Multilingual NN Results

Great results especially if we want to train a model to translate to a language that does not have a lot of available data for us (low resource language).

Unsupervised Learning for NLP

There are huge amounts of text without any labels and little of supervised data. How much can we learn about the language by just reading unlabelled text?

word2vec

Intuition - if words appear close together in the text, they are likely to be related, so we hope that by just looking at unlabelled English text, we can learn what they mean.

- Goal is to learn vector space representations for words (learn embeddings)

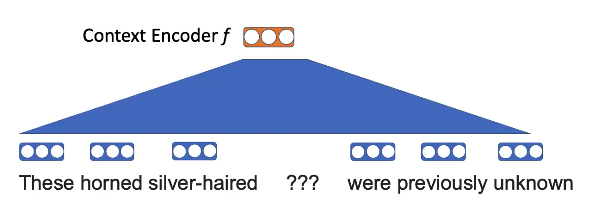

Pretraining task - mask some word and use neighbouring words to fill in the blanks.

Fig. 7: word2vec masking visual

For instance, here, the idea is that “horned” and “silver-haired” are more likely to appear in the context of “unicorn” than some other animal.

Take the words and apply a linear projection

Fig. 8: word2vec embeddings

Want to know

\[p(\texttt{unicorn} \mid \texttt{These silver-haired ??? were previously unknown})\] \[p(x_n \mid x_{-n}) = \text{softmax}(\text{E}f(x_{-n})))\]Word embeddings hold some structure

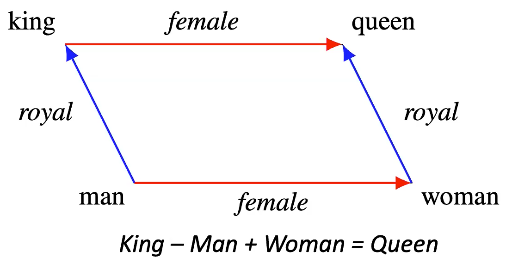

Fig. 9: Embedding structure example

- The idea is if we take the embedding for “king” after training and add the embedding for “female” we will get an embedding very close to that of “queen”

- Shows some meaningful differences between vectors

Question: Are the word representation dependent or independent of context?

Independent and have no idea how they relate to other words

Question: What would be an example of a situation that this model would struggle in?

Interpretation of words depends strongly on context. So in the instance of ambiguous words - words that may have multiple meanings - the model will struggle since the embeddings vectors won’t capture the context needed to correctly understand the word.

GPT

To add context, we can train a conditional language model. Then given this language model, which predicts a word at every time step, replace each output of model with some other feature.

- Pretraining - predict next word

- Fine-tuning - change to a specific task. Examples:

- Predict whether noun or adjective

- Given some text comprising an Amazon review, predict the sentiment score for the review

This approach is good because we can reuse the model. We pretrain one large model and can fine tune to other tasks.

ELMo

GPT only considers leftward context, which means the model can’t depend on any future words - this limits what the model can do quite a lot.

Here the approach is to train two language models

- One on the text left to right

- One on the text right to left

- Concatenate the output of the two models in order to get the word representation. Now can condition on both the rightward and leftward context.

This is still a “shallow” combination, and we want some more complex interaction between the left and right context.

BERT

BERT is similar to word2vec in the sense that we also have a fill-in-a-blank task. However, in word2vec we had linear projections, while in BERT there is a large transformer that is able to look at more context. To train, we mask 15% of the tokens and try to predict the blank.

Can scale up BERT (RoBERTa):

- Simplify BERT pre-training objective

- Scale up the batch size

- Train on large amounts of GPUs

- Train on even more text

Even larger improvements on top of BERT performance - on question answering task performance is superhuman now.

Pre-training for NLP

Let us take a quick look at different self-supervised pre training approaches that have been researched for NLP.

-

XLNet:

Instead of predicting all the masked tokens conditionally independently, XLNet predicts masked tokens auto-regressively in random order

-

SpanBERT

Mask spans (sequence of consecutive words) instead of tokens

-

ELECTRA:

Rather than masking words we substitute tokens with similar ones. Then we solve a binary classification problem by trying to predict whether the tokens have been substituted or not.

-

ALBERT:

A Lite Bert: We modify BERT and make it lighter by tying the weights across layers. This reduces the parameters of the model and the computations involved. Interestingly, the authors of ALBERT did not have to compromise much on accuracy.

-

XLM:

Multilingual BERT: Instead of feeding such English text, we feed in text from multiple languages. As expected, it learned cross lingual connections better.

The key takeaways from the different models mentioned above are

-

Lot of different pre-training objectives work well!

-

Crucial to model deep, bidirectional interactions between words

-

Large gains from scaling up pre-training, with no clear limits yet

Most of the models discussed above are engineered towards solving the text classification problem. However, in order to solve text generation problem, where we generate output sequentially much like the seq2seq model, we need a slightly different approach to pre training.

Pre-training for Conditional Generation: BART and T5

BART: pre-training seq2seq models by de-noising text

In BART, for pretraining we take a sentence and corrupt it by masking tokens randomly. Instead of predicting the masking tokens (like in the BERT objective), we feed the entire corrupted sequence and try to predict the entire correct sequence.

This seq2seq pretraining approach give us flexibility in designing our corruption schemes. We can shuffle the sentences, remove phrases, introduce new phrases, etc.

BART was able to match RoBERTa on SQUAD and GLUE tasks. However, it was the new SOTA on summarization, dialogue and abstractive QA datasets. These results reinforce our motivation for BART, being better at text generation tasks than BERT/RoBERTa.

Some open questions in NLP

- How should we integrate world knowledge

- How do we model long documents? (BERT-based models typically use 512 tokens)

- How do we best do multi-task learning?

- Can we fine-tune with less data?

- Are these models really understanding language?

Summary

- Training models on lots of data beats explicitly modelling linguistic structure.

From a bias variance perspective, Transformers are low bias (very expressive) models. Feeding these models lots of text is better than explicitly modelling linguistic structure (high bias). Architectures should be compressing sequences through bottlenecks

-

Models can learn a lot about language by predicting words in unlabelled text. This turns out to be a great unsupervised learning objective. Fine tuning for specific tasks is then easy

-

Bidirectional context is crucial

Additional Insights from questions after class:

What are some ways to quantify ‘understanding language’? How do we know that these models are really understanding language?

“The trophy did not fit into the suitcase because it was too big”: Resolving the reference of ‘it’ in this sentence is tricky for machines. Humans are good at this task. There is a dataset consisting of such difficult examples and humans achieved 95% performance on that dataset. Computer programs were able to achieve only around 60% before the revolution brought about by Transformers. The modern Transformer models are able to achieve more than 90% on that dataset. This suggests that these models are not just memorizing / exploiting the data but learning concepts and objects through the statistical patterns in the data.

Moreover, BERT and RoBERTa achieve superhuman performance on SQUAD and Glue. The textual summaries generated by BART look very real to humans (high BLEU scores). These facts are evidence that the models do understand language in some way.

Grounded Language

Interestingly, the lecturer (Mike Lewis, Research Scientist, FAIR) is working on a concept called ‘Grounded Language’. The aim of that field of research is to build conversational agents that are able to chit-chat or negotiate. Chit-chatting and negotiating are abstract tasks with unclear objectives as compared to text classification or text summarization.

Can we evaluate whether the model already has world knowledge?

‘World Knowledge’ is an abstract concept. We can test models, at the very basic level, for their world knowledge by asking them simple questions about the concepts we are interested in. Models like BERT, RoBERTa and T5 have billions of parameters. Considering these models are trained on a huge corpus of informational text like Wikipedia, they would have memorized facts using their parameters and would be able to answer our questions. Additionally, we can also think of conducting the same knowledge test before and after fine-tuning a model on some task. This would give us a sense of how much information the model has ‘forgotten’.

📝 Trevor Mitchell, Andrii Dobroshynskyi, Shreyas Chandrakaladharan, Ben Wolfson

20 Apr 2020