Visualization of neural networks parameter transformation and fundamental concepts of convolution

🎙️ Yann LeCunVisualization of neural networks

In this section we will visualise the inner workings of a neural network.

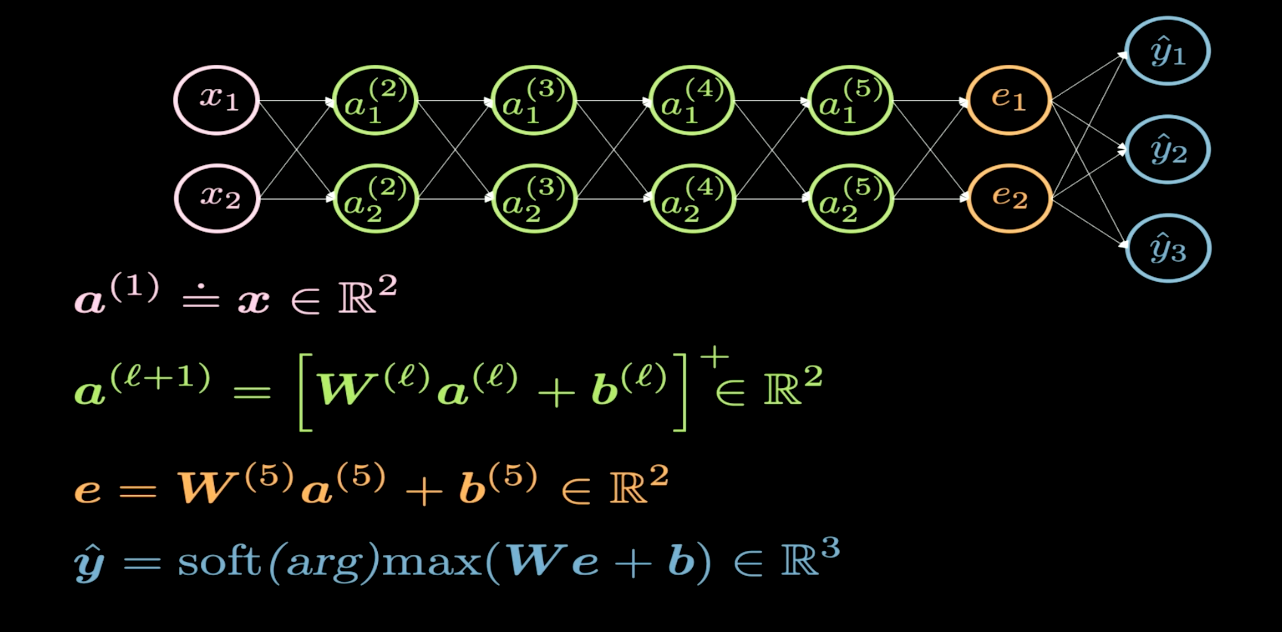

Fig. 1 Network Structure

Figure 1 depicts the structure of the neural network we would like to visualise. Typically, when we draw the structure of a neural network, the input appears on the bottom or on the left, and the output appears on the top side or on the right. In Figure 1, the pink neurons represent the inputs, and the blue neurons represent the outputs. In this network, we have 4 hidden layers (in green), which means we have 6 layers in total (4 hidden layers + 1 input layer + 1 output layer). In this case, we have 2 neurons per hidden layer, and hence the dimension of the weight matrix ($W$) for each layer is 2-by-2. This is because we want to transform our input plane into another plane that we can visualize.

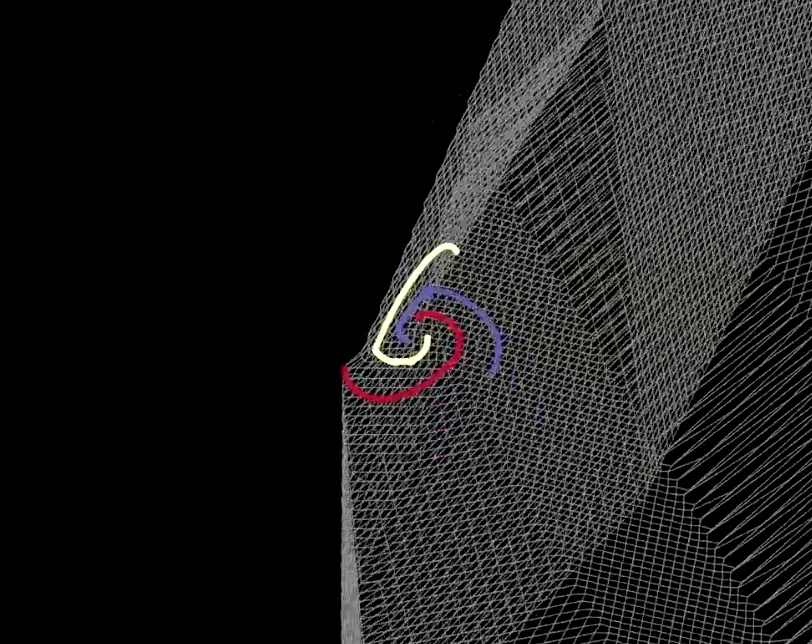

Fig. 2 Visualization of folding space

The transformation of each layer is like folding our plane in some specific regions as shown in Figure 2. This folding is very abrupt, this is because all the transformations are performed in the 2D layer. In the experiment, we find that if we have only 2 neurons in each hidden layer, the optimization will take longer; the optimization is easier if we have more neurons in the hidden layers. This leaves us with an important question to consider: Why is it harder to train the network with fewer neurons in the hidden layers? You should consider this question yourself and we will return to it after the visualization of $\texttt{ReLU}$.

|

|

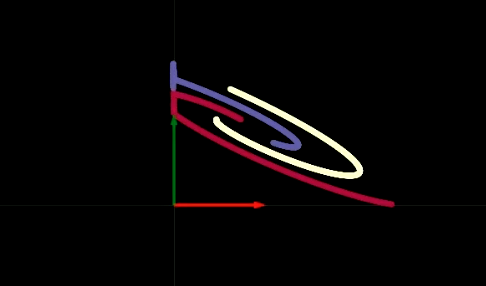

| (a) | (b) |

When we step through the network one hidden layer at a time, we see that with each layer we perform some affine transformation followed by applying the non-linear ReLU operation, which eliminates any negative values. In Figures 3(a) and (b), we can see the visualisation of ReLU operator. The ReLU operator helps us to do non-linear transformations. After mutliple steps of performing an affine transformation followed by the ReLU operator, we are eventually able to linearly separate the data as can be seen in Figure 4.

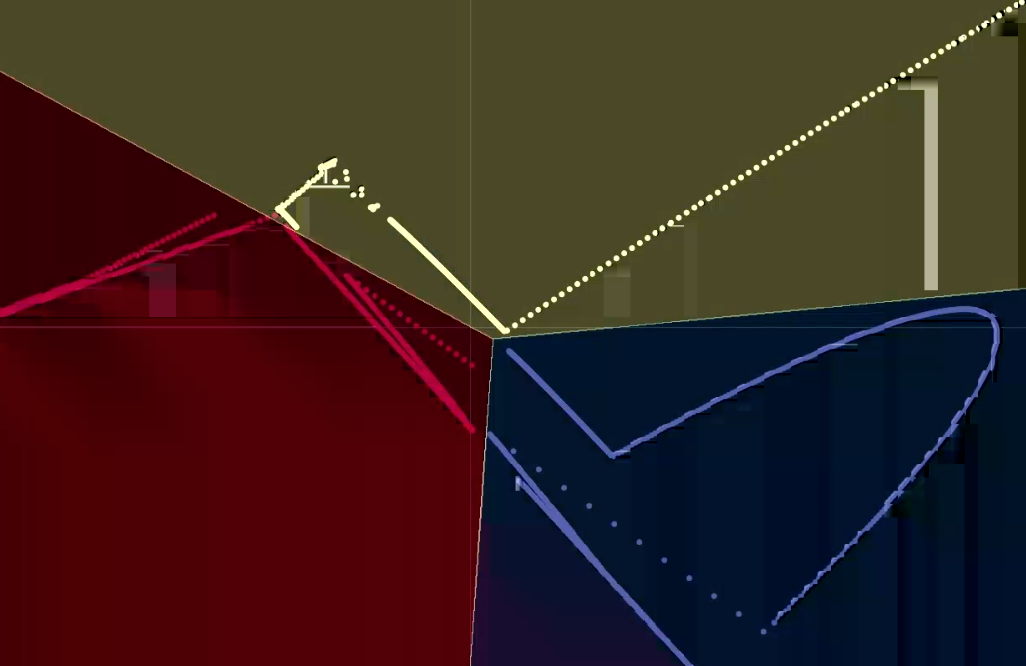

Fig. 4 Visualization of Outputs

This provides us with some insight into why the 2-neuron hidden layers are harder to train. Our 6-layer network has one bias in each hidden layers. Therefore if one of these biases moves points out of top-right quadrant, then applying the ReLU operator will eliminate these points to zero. After that, no matter how later layers transform the data, the values will remain zero. We can make a neural network easier to train by making the network “fatter” - i.e. adding more neurons in hidden layers - or we can add more hidden layers, or a combination of the two methods. Throughout this course we will explore how to determine the best network architecture for a given problem, stay tuned.

Parameter transformations

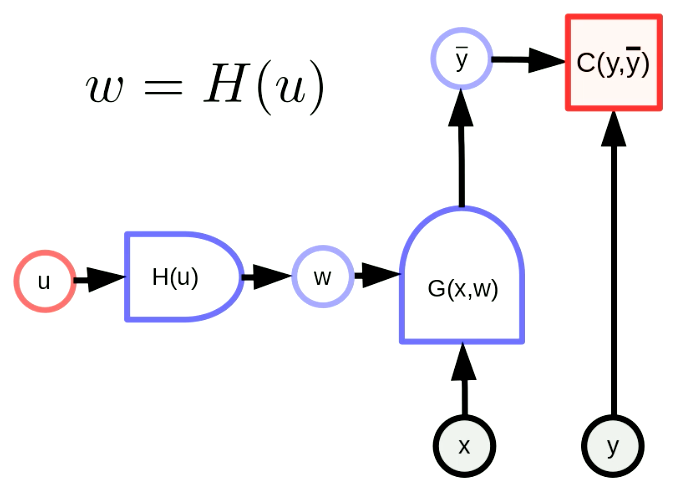

General parameter transformation means that our parameter vector $w$ is the output of a function. By this transformation, we can map original parameter space into another space. In Figure 5, $w$ is actually the output of $H$ with the parameter $u$. $G(x,w)$ is a network and $C(y,\bar y)$ is a cost function. The backpropagation formula is also adapted as follows,

\[u \leftarrow u - \eta\frac{\partial H}{\partial u}^\top\frac{\partial C}{\partial w}^\top\] \[w \leftarrow w - \eta\frac{\partial H}{\partial u}\frac{\partial H}{\partial u}^\top\frac{\partial C}{\partial w}^\top\]These formulas are applied in a matrix form. Note that the dimensions of the terms should be consistent. The dimension of $u$,$w$,$\frac{\partial H}{\partial u}^\top$,$\frac{\partial C}{\partial w}^\top$ are $[N_u \times 1]$,$[N_w \times 1]$,$[N_u \times N_w]$,$[N_w \times 1]$, respectively. Therefore, the dimension of our backpropagation formula is consistent.

Fig. 5 General Form of Parameter Transformations

A simple parameter transformation: weight sharing

A Weight Sharing Transformation means $H(u)$ just replicates one component of $u$ into multiple components of $w$. $H(u)$ is like a Y branch to copy $u_1$ to $w_1$, $w_2$. This can be expressed as,

\[w_1 = w_2 = u_1, w_3 = w_4 = u_2\]We force shared parameters to be equal, so the gradient w.r.t. to shared parameters will be summed in the backprop. For example the gradient of the cost function $C(y, \bar y)$ with respect to $u_1$ will be the sum of the gradient of the cost function $C(y, \bar y)$ with respect to $w_1$ and the gradient of the cost function $C(y, \bar y)$ with respect to $w_2$.

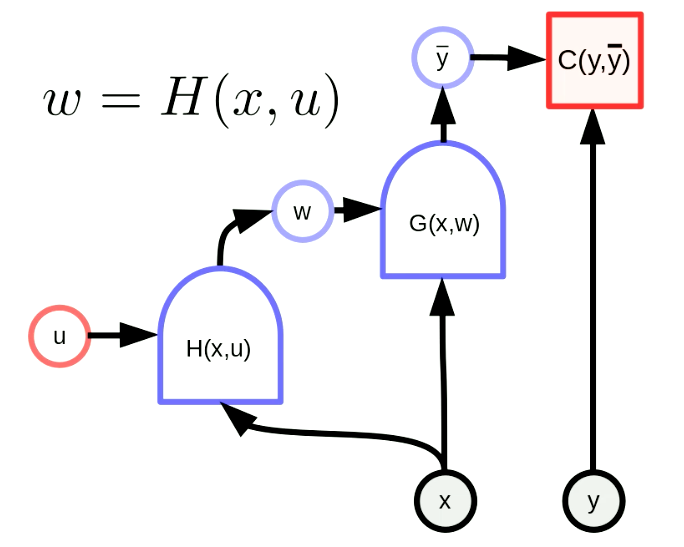

Hypernetwork

A hypernetwork is a network where the weights of one network is the output of another network. Figure 6 shows the computation graph of a “hypernetwork”. Here the function $H$ is a network with parameter vector $u$ and input $x$. As a result, the weights of $G(x,w)$ are dynamically configured by the network $H(x,u)$. Although this is an old idea, it remains very powerful.

Fig. 6 "Hypernetwork"

Motif detection in sequential data

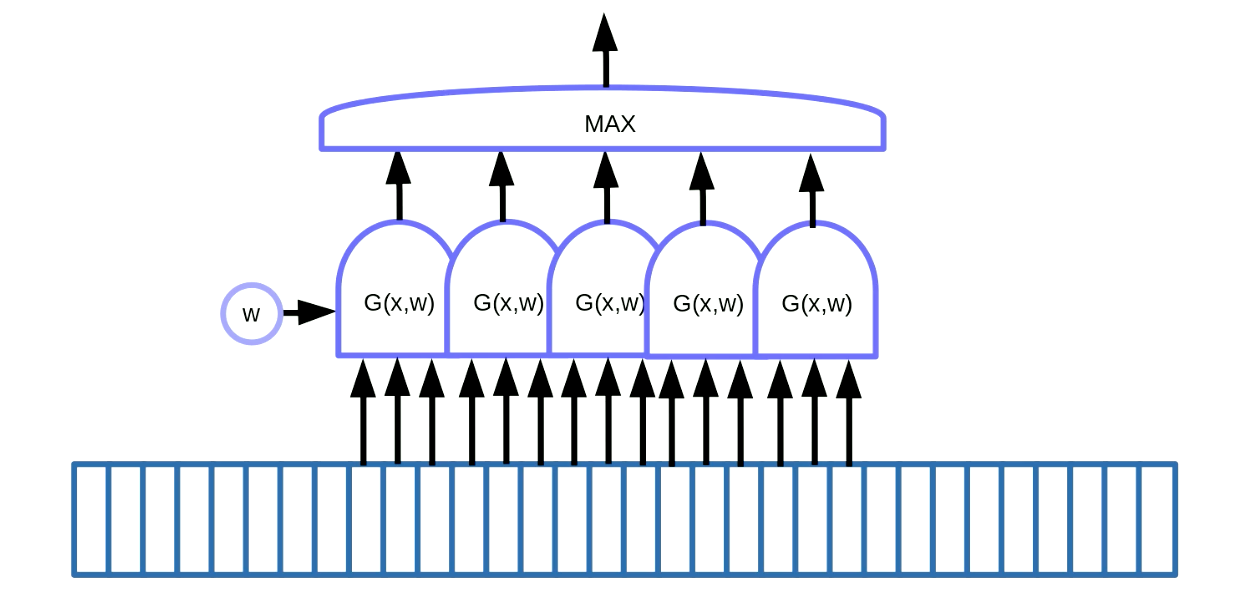

Weight sharing transformation can be applied to motif detection. Motif detection means to find some motifs in sequential data like keywords in speech or text. One way to achieve this, as shown in Figure 7, is to use a sliding window on data, which moves the weight-sharing function to detect a particular motif (i.e. a particular sound in speech signal), and the outputs (i.e. a score) goes into a maximum function.

Fig. 7 Motif Detection for Sequential Data

In this example we have 5 of those functions. As a result of this solution, we sum up five gradients and backpropagate the error to update the parameter $w$. When implementing this in PyTorch, we want to prevent the implicit accumulation of these gradients, so we need to use zero_grad() to initialize the gradient.

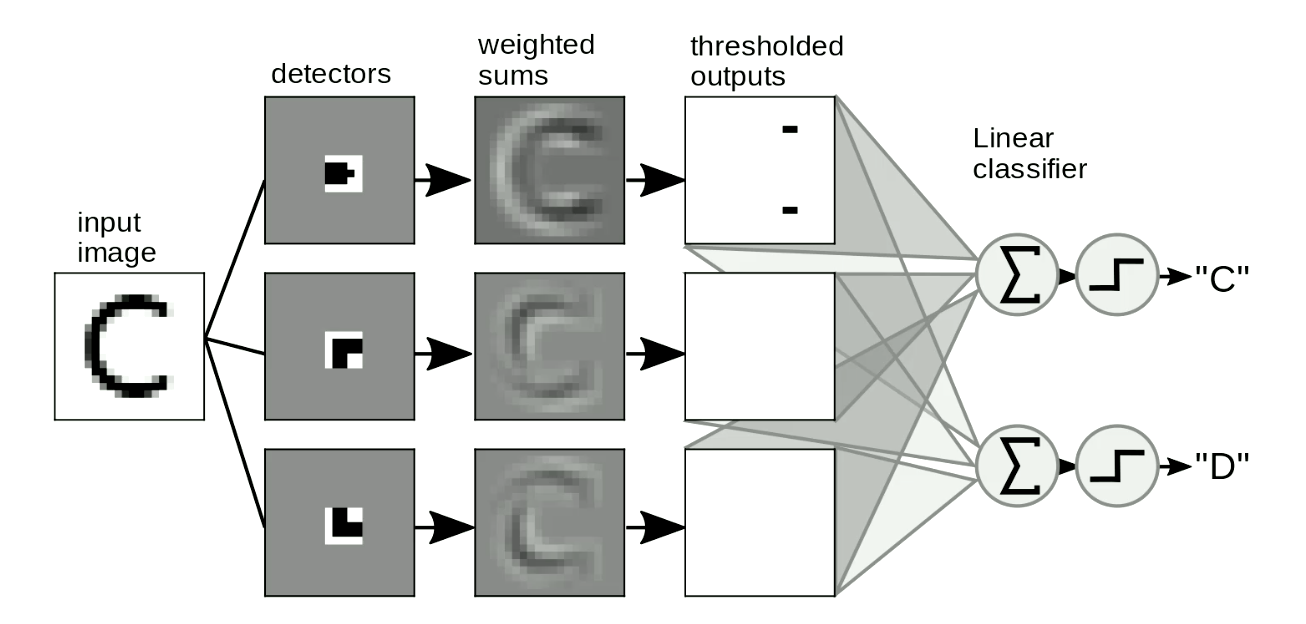

Motif detection in images

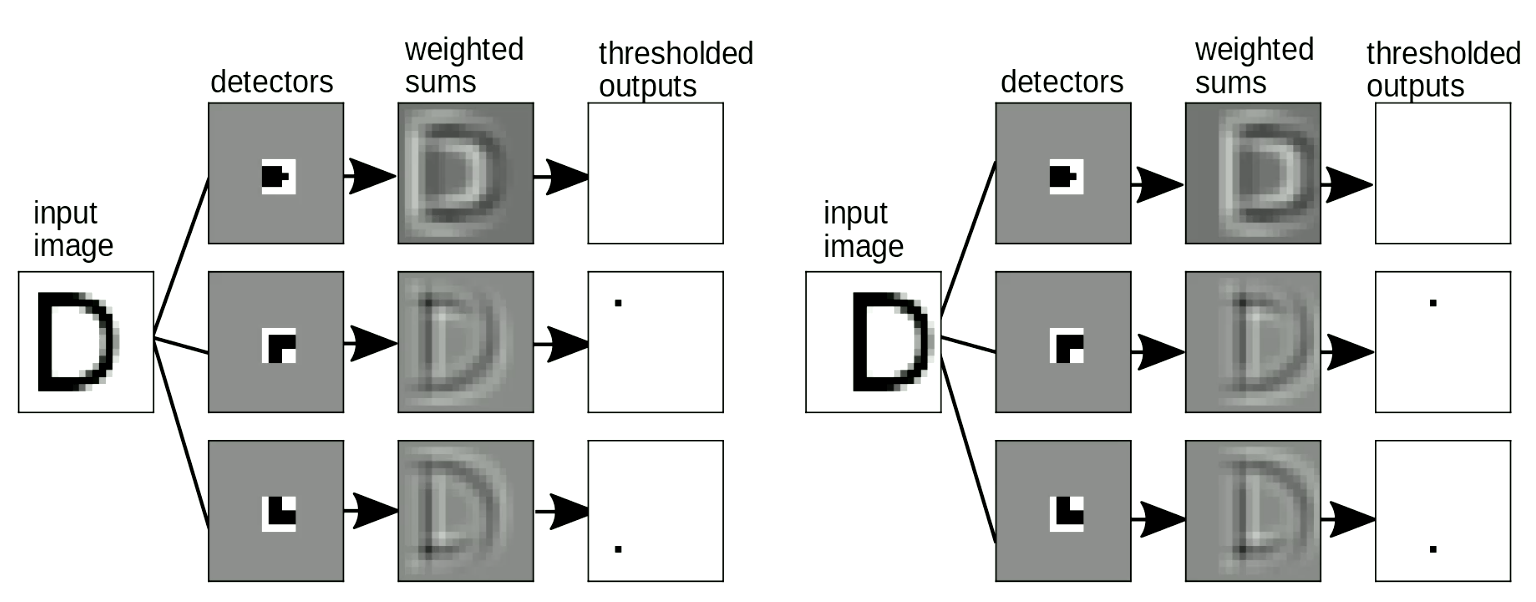

The other useful application is motif detection in images. We usually swipe our “templates” over images to detect the shapes independent of position and distortion of the shapes. A simple example is to distinguish between “C” and “D”, as Figure 8 shows. The difference between “C” and “D” is that “C” has two endpoints and “D” has two corners. So we can design “endpoint templates” and “corner templates”. If the shape is similar to the “templates”, it will have thresholded outputs. Then we can distinguish letters from these outputs by summing them up. In Figure 8, the network detects two endpoints and zero corners, so it activates “C”.

Fig. 8 Motif Detection for Images

It is also important that our “template matching” should be shift-invariant - when we shift the input, the output (i.e. the letter detected) shouldn’t change. This can be solved with weight sharing transformation. As Figure 9 shows, when we change the location of “D”, we can still detect the corner motifs even though they are shifted. When we sum up the motifs, it will activate the “D” detection.

Fig. 9 Shift Invariance

This hand-crafted method of using local detectors and summation to for digit-recognition was used for many years. But it presents us with the following problem: How can we design these “templates” automatically? Can we use neural networks to learn these “templates”? Next, We will introduce the concept of convolutions , that is, the operation we use to match images with “templates”.

Discrete convolution

Convolution

The precise mathematical definition of a convolution in the 1-dimensional case between input $x$ and $w$ is:

\[y_i = \sum_j w_j x_{i-j}\]In words, the $i$-th output is computed as the dot product between the reversed $w$ and a window of the same size in $x$. To compute the full output, start the window at the beginning, shift this window by one entry each time and repeat until $x$ is exhausted.

Cross-correlation

In practice, the convention adopted in deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch is slightly different. Convolution in PyTorch is implemented where $w$ is not reversed:

\[y_i = \sum_j w_j x_{i+j}\]Mathematicians call this formulation “cross-correlation”. In our context, this difference is just a difference in convention. Practically, cross-correlation and convolution can be interchangeable if one reads the weights stored in memory forward or backward.

Being aware of this difference is important, for example, when one want to make use of certain mathematical properties of convolution/correlation from mathematical texts.

Higher dimensional convolution

For two dimensional inputs such as images, we make use of the two dimensional version of convolution:

\[y_{ij} = \sum_{kl} w_{kl} x_{i+k, j+l}\]This definition can easily be extended beyond two dimensions to three or four dimensions. Here $w$ is called the convolution kernel

Regular twists that can be made with the convolutional operator in DCNNs

- Striding: instead of shifting the window in $x$ one entry at a time, one can do so with a larger step (for example two or three entries at a time). Example: Suppose the input $x$ is one dimensional and has size of 100 and $w$ has size 5. The output size with a stride of 1 or 2 is shown in the table below:

| Stride | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Output size: | $\frac{100 - (5-1)}{1}=96$ | $\frac{100 - (5-1)}{2}=48$ |

- Padding: Very often in designing Deep Neural Networks architectures, we want the output of convolution to be of the same size as the input. This can be achieved by padding the input ends with a number of (typically) zero entries, usually on both sides. Padding is done mostly for convenience. It can sometimes impact performance and result in strange border effects, that said, when using a ReLU non-linearity, zero padding is not unreasonable.

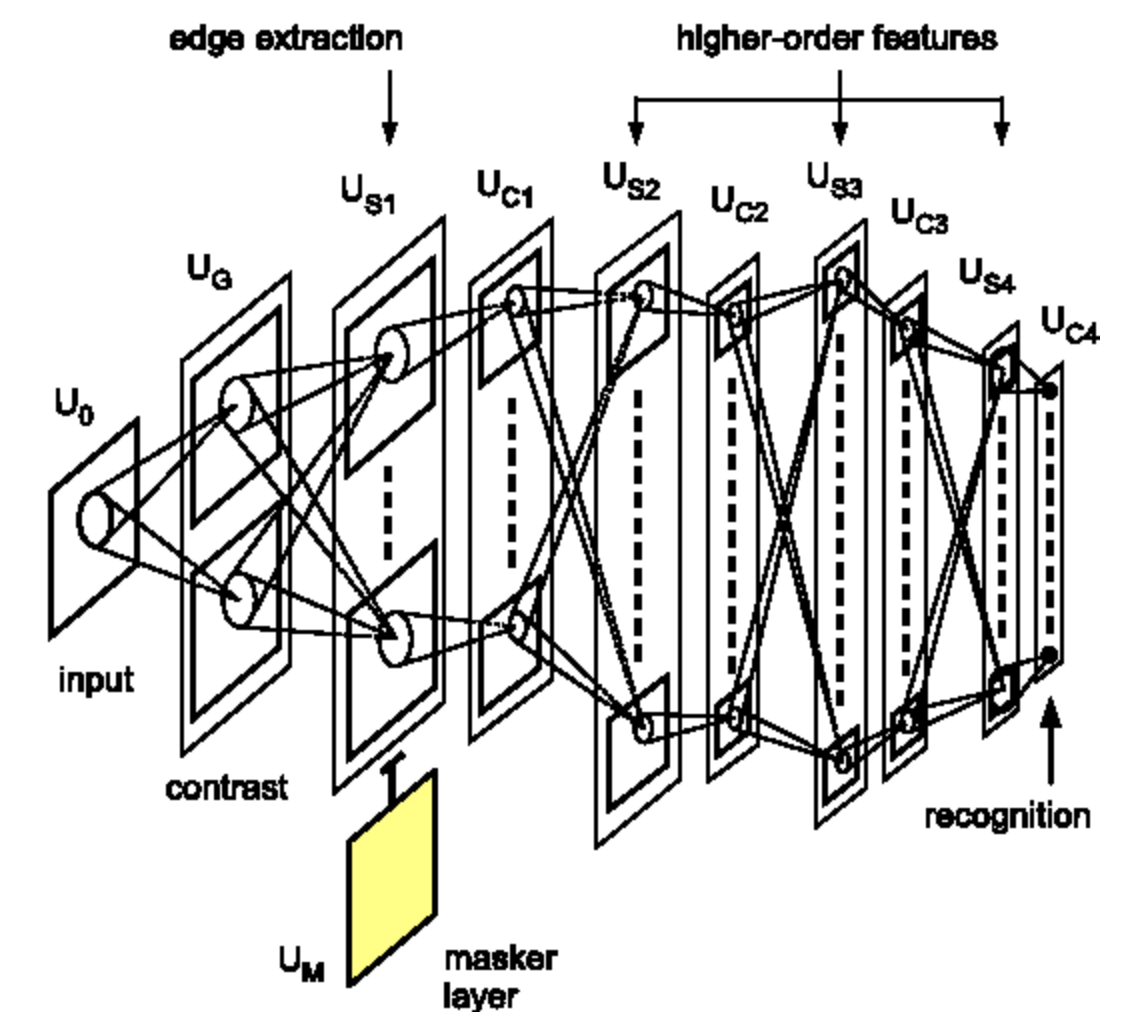

Deep Convolution Neural Networks (DCNNs)

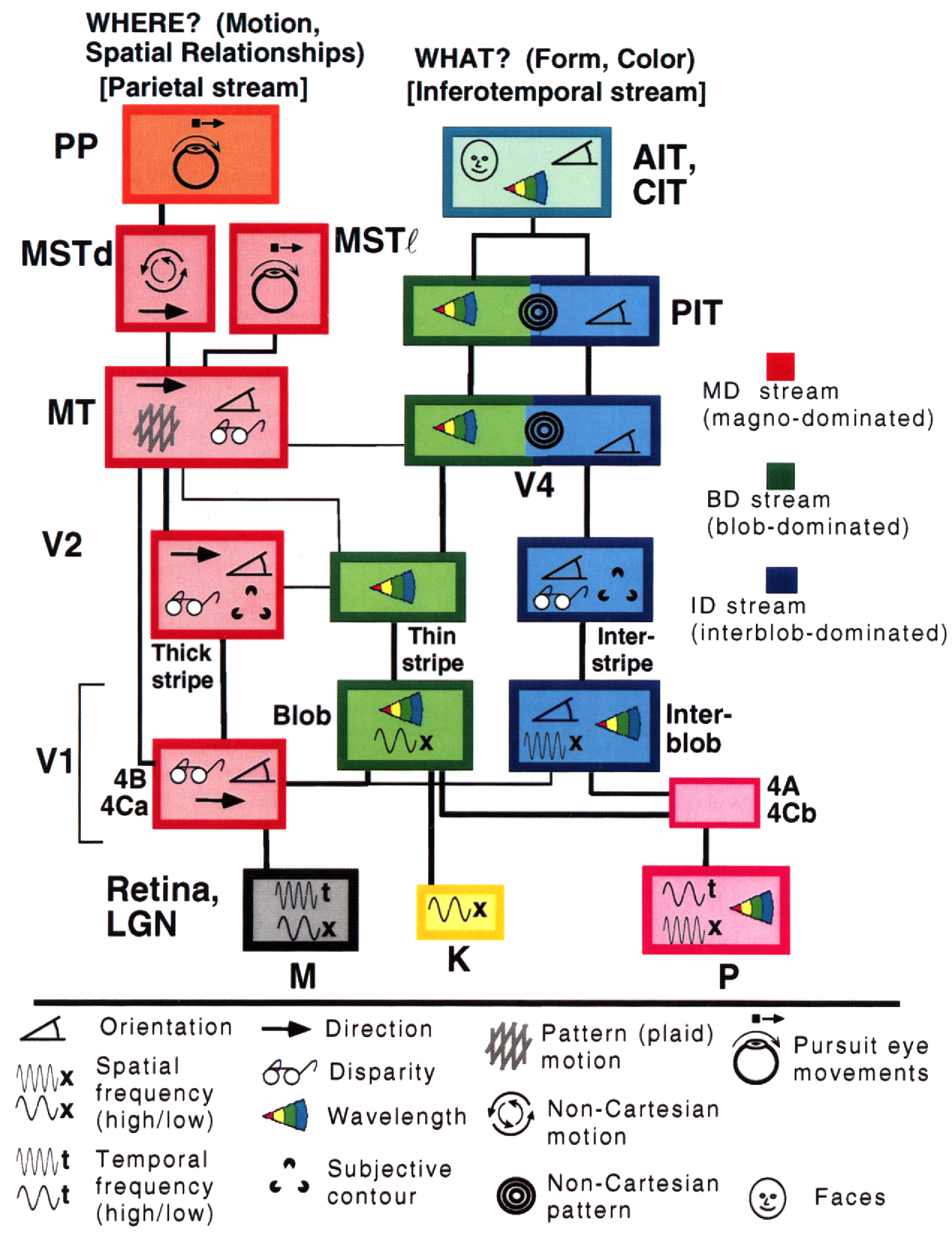

As previously described, deep neural networks are typically organized as repeated alternation between linear operators and point-wise nonlinearity layers. In convolutional neural networks, the linear operator will be the convolution operator described above. There is also an optional third type of layer called the pooling layer.

The reason for stacking multiple such layers is that we want to build a hierarchical representation of the data. CNNs do not have to be limited to processing images, they have also been successfully applied to speech and language. Technically they can be applied to any type of data that comes in the form of arrays, although we also these arrays to satisfy certain properties.

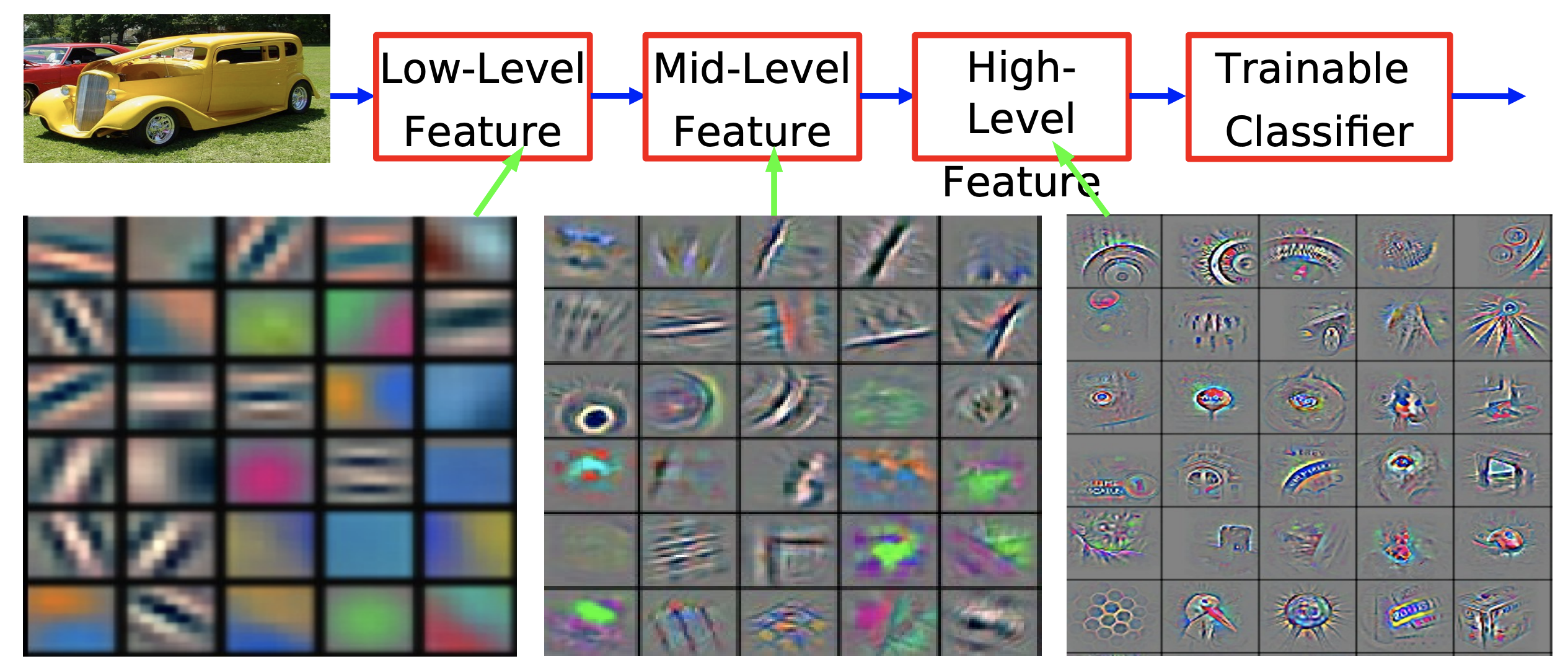

Why would we want to capture the hierarchical representation of the world? Because the world we live in is compositional. This point is alluded to in previous sections. Such hierarchical nature can be observed from the fact that local pixels assemble to form simple motifs such as oriented edges. These edges in turn are assembled to form local features such as corners, T-junctions, etc. These edges are assembled to form motifs that are even more abstract. We can keep building on these hierarchical representation to eventually form the objects we observe in the real world.

Figure 10. Feature visualization of convolutional net trained on ImageNet from [Zeiler & Fergus 2013]

This compositional, hierarchical nature we observe in the natural world is therefore not just the result of our visual perception, but also true at the physical level. At the lowest level of description, we have elementary particles, which assembled to form atoms, atoms together form molecules, we continue to build on this process to form materials, parts of objects and eventually full objects in the physical world.

The compositional nature of the world might be the answer to Einstein’s rhetorical question on how humans understand the world they live in:

The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.

The fact that humans understand the world thanks to this compositional nature still seems like a conspiracy to Yann. It is, however, argued that without compositionality, it will take even more magic for humans to comprehend the world they live in. Quoting the great mathematician Stuart Geman:

The world is compositional or God exists.

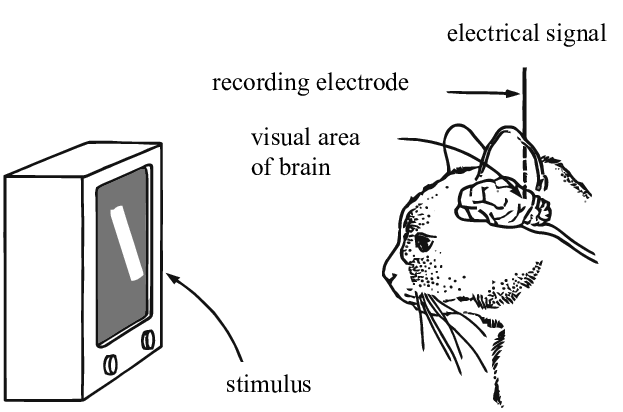

Inspirations from Biology

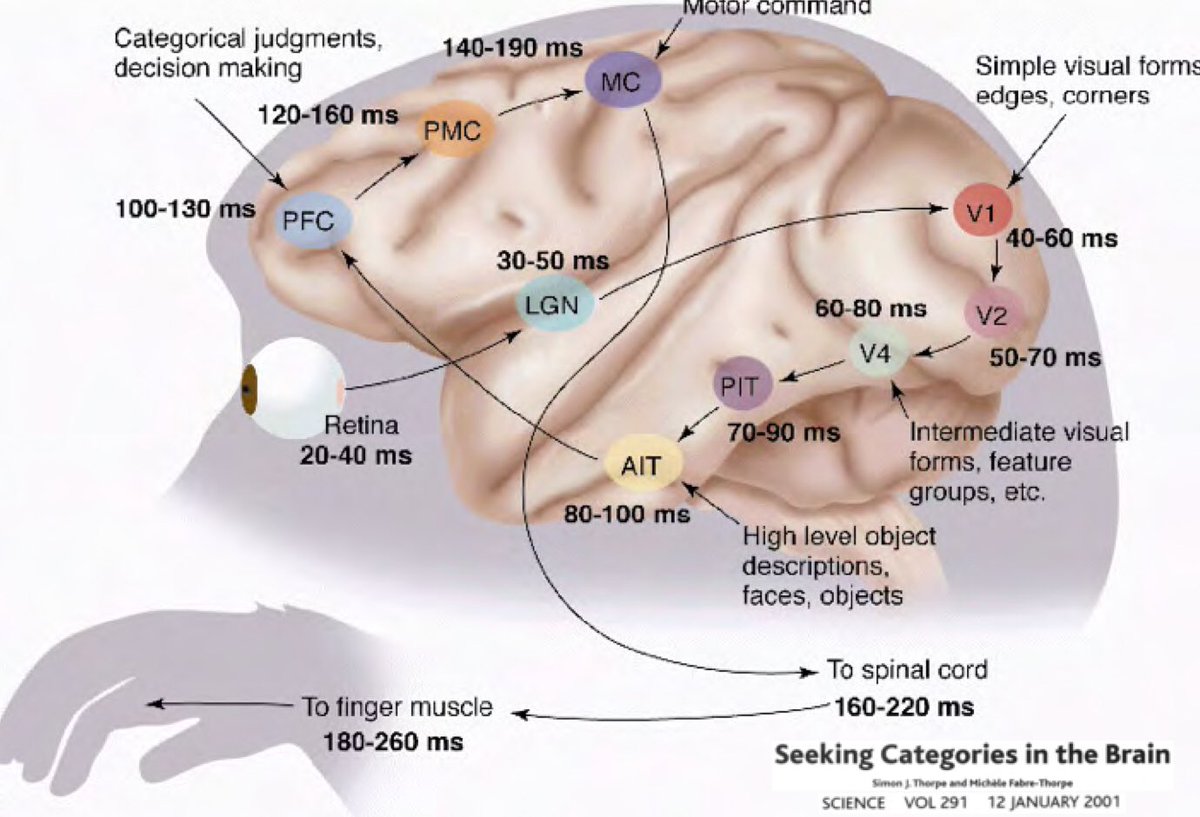

So why should Deep Learning be rooted in the idea that our world is comprehensible and has a compositional nature? Research conducted by Simon Thorpe helped motivate this further. He showed that the way we recognize everyday objects is extremely fast. His experiments involved flashing a set of images every 100ms, and then asking users to identify these images, which they were able to do successfully. This demonstrated that it takes about 100ms for humans to detect objects. Furthermore, consider the diagram below, illustrating parts of the brain annotated with the time it takes for neurons to propagate from one area to the next:

📝 Jiuhong Xiao, Trieu Trinh, Elliot Silva, Calliea Pan

10 Feb 2020