Running SN on Apple silicon

After reading the 1998 SN article, you may wonder if such code still runs. The answer is “Yes!” and that’s how figure 2 was generated. And in this blog we’ll learn how to run the paper’s code, back-ported as a package into the 2002 Lush codebase.

Why running old code

Besides the personal archaeological and reverse engineering interests, one may want to run ancient code to see how the algorithms we call these days “AI” are nothing new, and they were in fact already actively developed ~40 years ago. Due to the hardware computing limitations, the software needed to be very efficient. Yet, for aiding the scientist, visualisations and model inspections functionalities were present to facilitate comprehension of the experimental results. Therefore, we can learn about the authors software design principles, who created a tool to suit their own needs, when tools for the task were not available, closed-source, or simply not flexible enough. Finally, SN is the precursor of Torch, which is the father of PyTorch. So, we can consider SN the grandfather of PyTorch, therefore making this a family story.

On a personal note, when doing my PhD, “no one told me” reading someone else’s code was a thing. Fast-forward a decade, and now to understand papers I “simply” read their implementation. Things can be explained with pictures, English, maths, and code. Eventually, code is what is run to produce a result. Therefore, reading code should be normalised, if it’s not yet a thing (no, I don’t have a Computer Science background, so I’ve been figuring things out by my own).

Dependencies

I’ll assume you have brew already installed on your system.

If this is not the case, head over to Homebrew webpage and follow the installation instructions.

Then, in your terminal, type the following:

brew install subversion gnu-indent readline xquartz

cd to your working directory and run the following commands to fetch and compile Lush, which is the most recent incarnation and merging of all SN versions.

svn checkout https://svn.code.sf.net/p/lush/code/lush1/trunk lush

cd lush ; ./configure ; make -j4

You should be able to execute ./bin/lush, which welcomes you with:

LUSH Lisp Universal Shell (compiled on Aug 6 2024)

Copyright (C) 2002 Leon Bottou, Yann LeCun, AT&T, NECI.

Consider creating a link to this into your ~/bin directory (assuming you have one in your PATH).

That way you can just type lush to invoke the interpreter.

Type ^D y ⏎ to quit for now.

Reading the manual

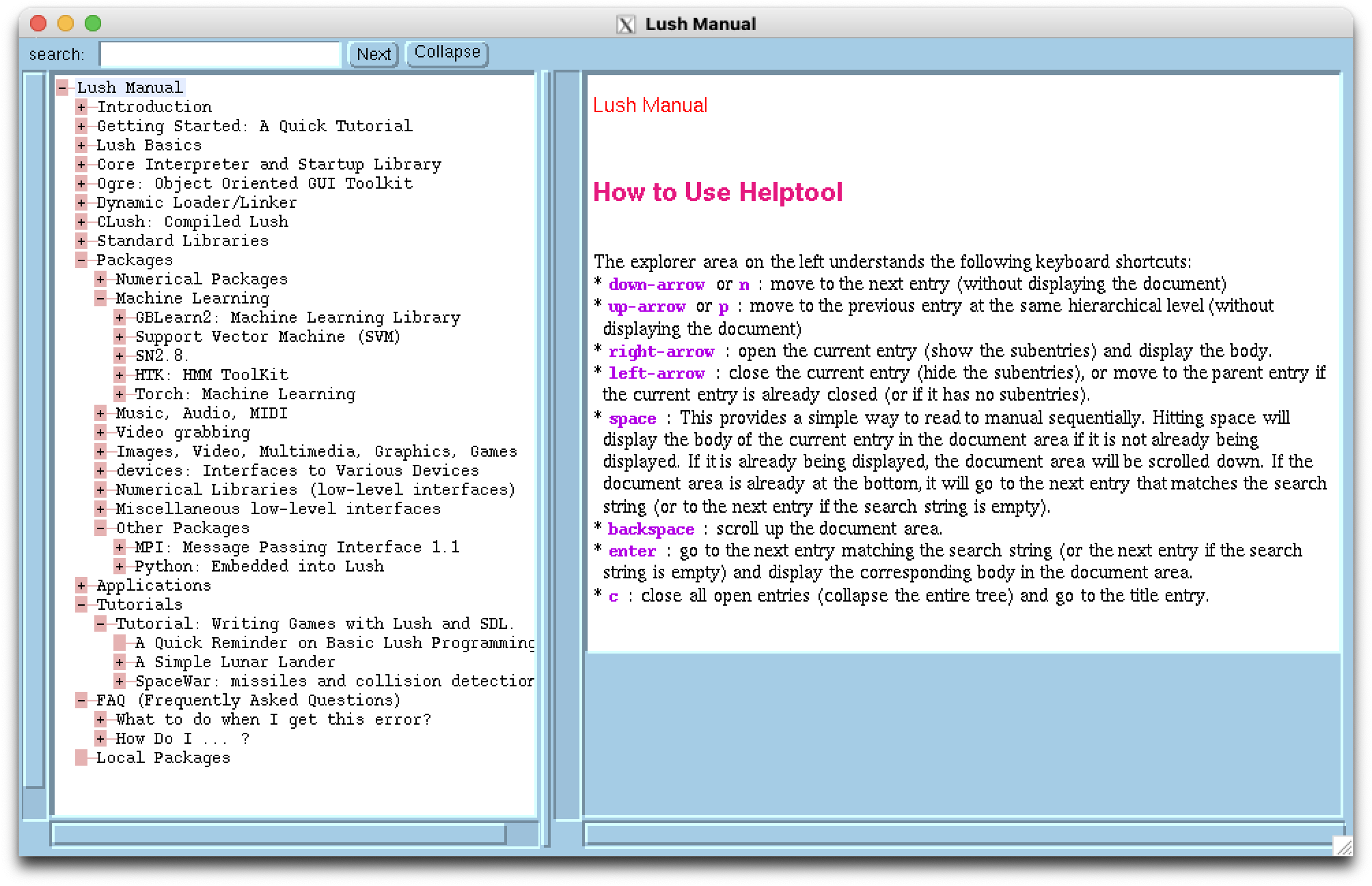

To test the graphical abilities of Lush, let’s run its manual.

First, we need to run XQuartz.

Then we can invoke lush and type the command (helptool) ⏎.

The following window should pop up.

Noticeable Packages are Torch, under the Machine Learning section, Python support, in the Other Packages, and the presence of Tutorials on how to create games, for possibly training your controller on.

The 1998 SN article’s code

The example code of section 8 of the 1998 SN article trains (the paper use the word simulates) a fully-connected autoencoder (or multilayer network operating in auto-association) with 4 binary input neurons, 2 hidden neurons, and 4 output neurons.

Both hidden and output layers have a scaled hyperbolic tangent as non-linearity.

The objective is to encode 4 4-bits patters, i.e. +---, -+--, --+-, ---+, into two hidden binary units.

Running the code

A slightly updated version of the code from the article can be found at the following location:

lush/packages/sn28/examples/autoenc/autoenc.sn

If you read the code with Vim, you may want to

:set filetype=lispto turn on the syntax highlighting. To make this option automatic, addau BufRead,BufNewFile *.sn setl filetype=lispto your~/.vimrc. If you use Visual Studio Code, you may want to install the Lisp extension, openautoenc.sn, either click onPlain Texton the status bar or press⌘KM, and select Lisp as Language Mode.

To run the code and prevent the windows to close when the training completes, run lush from within autoenc.sn’s directory and type the following:

(load "autoenc")

You’ll see the training logs scrolling on your terminal, the line plot displaying the current training loss, and the additional graphic window showing the values for the 4 input neurons at the bottom, the 2 hidden units in the centre, and the 4 output neurons at the top, colour coded such that white corresponds to +1 and black to −1.

If you want to get exactly the results shown in this and in the 1998 SN article blog posts, add

;;; CHEAT (for blog writing purpose)

(seed 314)

right after the two libload lines.

Let’s have a look at the output corresponding at iteration (age) 49, which is generated by disp-basic-iteration, called bybasic-iteration, called by learn, the last line of code in autoenc.sn.

To read the source code for these these functions, you can run (pretty <function name>).

X : 1.047 -1.668 -0.689 -1.230

Y : -0.033 0.087 -0.287 0.123

age=49 pattern=0 error= 0.07476 ok

The first line of disp-basic-iteration is (print-layer output-layer), which displays the output-layer neuron-values nval labelled as X and the corresponding gradients ngrad labelled Y.

The current pattern-number is 0, meaning we’re currently feeding the pattern P: +1 -1 -1 -1 to our model.

The model output is the list X.

The error cost is computed by do-compute-err, called by backward-prop, called by basic-iteration.

More precisely, $C(\bm{x}, \bm{p}) = 0.5 \, \Vert \bm{x} - \bm{p} \Vert^2 / 4 \simeq 0.07476$, where $\bm{x}$ and $\bm{p}$ are the output and pattern vectors respectively.

The final ok is telling us that the mean squared distance between the $\bm{x}$ and $\bm{p}$ is less than 0.2.

This check is performed by class-lms, called by classify, called by basic-iteration, which assigns True to good-answer when such condition holds.

And indeed $2 \cdot C(\bm{x}, \bm{p}) \simeq 0.15 < 0.20$.

Let’s move to the gradient line, which is going to give us a headache.

First, the output X is the last linear sum $\bm{s}$ to which a non-linear function nlf $f(\cdot)$, configured with (nlf-tanh 0.666 0.05), is applied.

In other words, $\bm{x} = f(\bm{s})$.

In our case, $f(s) = 1.58 \, \tanh(2/3 \, s) + 0.05\,s$.

This means that $\partial C / \partial \bm{s} \doteq \bm{y} = (\bm{p} - \bm{x})\,f’(\bm{s})$.

The analytical derivative is $f’(s) = 1.58\cdot2/3 \, (1 - \tanh^2(2/3\, s)) + 0.05$.

Assuming we know the values for $\bm{s}$ (which is not quite true), we get that

$\partial C / \partial \bm{s} \simeq \langle -0.032, 0.086, -0.287, 0.123 \rangle$,

which is reasonably close to what we see from the log.

During the forward pass we do compute $\bm{s} = \bm{W} \bm{h}$, with $\bm{h}$ being the hidden layer, and we store its value such that it is available for the backprop pass. Since we’re doing things post mortem (the weights have changed two times since these logs were generated), we need to find out $\bm{s}$ from $\bm{x}$, by inverting $f(\cdot)$, which is a little tricky. We can perform such inversion by defining $g(s, x) = f(s) - x$, where $x$ is the expected output. Then, we use the Newton–Raphson method to find the root of $g$, starting for example at $s=0$. If we apply this method to each value of

Xwe get $\bm{s} \simeq \langle 1.106, -2.957, -0.663, -1.406 \rangle$. Finally, to make sure everything works out, we can computeX: $f(\bm{s}) \simeq \langle 1.047, -1.668, -0.689, -1.230 \rangle$, which matches what we see in the log above.from scipy.optimize import newton f = lambda s: 1.58 * tanh(2/3 * s) + 0.05 * s df = lambda s: 1.58 * 2/3 * (1 - tanh(2/3 * s)**2) + 0.05 g = lambda s, x: f(s) - x dg = lambda s, x: df(s) s0 = 0 X = array([1.047, -1.668, -0.689, -1.230]) S = array([newton(g, s0, fprime=dg, args=(x,)) for x in X]) P = array([+1, -1, -1, -1]) Y = (P - X) * df(S) print(S, f(S), Y, sep='\n') # [ 1.10629125 -2.95915082 -0.66264701 -1.40597844] # [ 1.047 -1.668 -0.689 -1.230] # [-0.03235385 0.08578894 -0.28668920 0.12324831]

That was intense 😳!

Now that we understand what’s going on, let’s have a look at the 50th and last iteration.

X : -1.725 0.046 -1.014 -0.911

Y : 0.065 1.051 0.010 -0.070

age=50 pattern=1 error= 0.18043 **arrgh**

The cost $C(\bm{x}, \bm{p}) \simeq 0.18048$, $2 \cdot C(\bm{x}, \bm{p}) \simeq 0.36 > 0.20$, which gives us the **arrgh** message, and the gradients wrt the linear output are

$\partial C / \partial \bm{s} \simeq \langle 0.0647, 1.052, 0.010, -0.070 \rangle$.

Again, the final gradients were computed by the following code.

X = array([-1.725, 0.046, -1.014, -0.911]) S = array([newton(g, s0, fprime=dg, args=(x,)) for x in X]) P = array([-1, +1, -1, -1]) Y = (P - X) * df(S) print(S, f(S), Y, sep='\n') [-3.49369353 0.0417021 -1.05921493 -0.92200265] [-1.725 0.046 -1.014 -0.911] [ 0.06467563 1.05180371 0.00999082 -0.07010527]

To figure these things out, I’ve read:

- the manual accessible via the

(helptool)command, - some Lisp source code via

(pretty <function name>) - the network-environment Lisp source code accessible at:

lush/packages/sn28/lib/netenv.sn - and the non-linear function C source code you can find at:

packages/sn28/src/nlf.c

A few more notes on the learning script

The autoencoder script, stripped from its comments and displaying routines, it’s a dozen lines of code.

Such coding hygiene allows the user to focus on the science rather than on writing boiler plate code.

If we inspect the definition of learn we have:

(de learn (it)

(repeat it

; perform a basic-iteration on the current-pattern

(basic-iteration current-pattern)

; pick new patter for the next iteration

(setq current-pattern (next-pattern current-pattern)) )

(list it) )

and basic-iteration is where the standard learning pipeline takes place:

(de basic-iteration (n)

; get a pattern

(present-pattern input-layer n)

; propagates the states

(forward-prop net-struc)

; get the desired output

(present-desired desired-layer n)

; computes local-error and initializes the gradients

(do-compute-err output-layer desired-layer)

; propagates the gradients

(backward-prop net-struc)

; update the weights

(do-update-weight net-struc)

; increments "age"

(incr age)

; computes "good answer"

(setq good-answer (classify n))

; display functions

(process-pending-events)

(disp-basic-iteration)

local-error)

One could keep going down the rabbit hole and look into all these subroutines. But for what concerns this blog post, we’ve reached an end. We’ve read some source code in Lisp and C, we have numerically verify the correctness of the logs, and we have had the opportunity to witness one of the earliest instances of adapting the synaptic weights of an artificial neural network.

How to cite this blog

@misc{canziani2024SN-code,

author = {Canziani, Alfredo and Bottou, Léon},

title = {{Running SN on Apple silicon}},

howpublished = {\url{https://atcold.github.io/2024/08/09/SN-code}},

note = {Accessed: <date>},

year = {2024}

}